Passenger Voyage – Palermo to New Orleans 1900

According to newspaper articles written at the time, the ship named Olbia sailed out of Palermo on June 13th of 1900, arrived to quarantine on the 7th of June, then pulled up and anchored midstream near Algiers Point in New Orleans on the 8th of July.

No passengers were allowed to leave the ship until the10thof July. At that point they had been aboard almost a month, and some were required to remain on the ship even longer than that.

The Olbia arrival was big news in July of 1900 as there were numerous newspaper articles written about it and its issues throughout the month, particularly since the process took exceedingly long. The ship wasn’t even allowed to leave New Orleans for a couple of weeks after arrival. There was much outcry about it and the extreme conditions endured, and improvements were thereafter made.

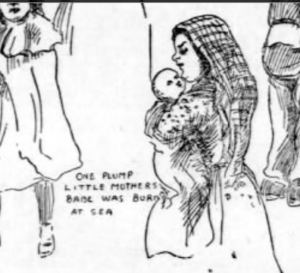

Below are some sketches from a newspaper article at the time of some of the passengers on that particular voyage.

Anchored Midstream

Unlike Ellis Island in New York, New Orleans had no immigration station in those early years to process the increasingly large numbers of immigrants arriving. So after making the long, arduous journey, they were then required to stay on the ship midstream while all the inspections took place. The inspectors rowed out to the ship each day, and all inspections took place on the ship.

For quick inspections after which new immigrants could quickly disembark, it was relief to step on new land and new life after 3 or more weeks on the crowded voyage, particularly for those in steerage (which is the how the majority traveled). Unfortunately for those on the Olbia, those inspections took much longer than normal, but helped lead to improvements for future immigrants arriving in New Orleans.

The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana) 09 July 1900 (Monday) stated that the steamship Olbia anchored midstream opposite the Ursulines Convent.

Excerpts from the articles help provide a comprehensive view of what immigrants arriving into New Orleans at the time went through, including discussion of the physical examinations, the interrogations, and the baggage inspections.

The Voyage

Captain Mattel, commander of the Olbia, said that the trip from Palermo to New Orleans was devoid any unpleasant or untoward incident. The voyage was made in twenty-three days. The weather was very favorable, and not a single case of sickness declared itself. The immigrants proved docile, quiet, well behaved and satisfied.

During the voyage a stranger was discovered aboard. The name was not on the ship’s list when the vessel left Palermo, and it was only in midocean that Captain Mattel was apprised of the fact that there was one more human being on the ship, and that the addition would have to be accounted for the United States government, which imposes a fine of $1000 for every passenger in excess of the ship’s list.

So the captain went among the immigrants and found the stranger in close companionship with Felipe Abruzzi and Marie Abruzzi, and he asked them the name of the stranger. “We do not know,” they said; “ask her, but we are afraid she cannot talk” Captain Mattel came nearer, and looked at the addition to the ship’s list. What did he see? A small, rosy, dimpled, pretty babe, a girl, born to the young couple just named; born at sea, and of course to be classed as “native of France,” for she had opened her eyes to the mundane scenes and sights on board of a ship flying the flag of France. Seeing that she was only a wee babe, and not a disturber of his peace of mind and of his pocketbook, and that he would not have to pay a thousand dollars fine to the United States government, the captain smiled and, bending low, kissed the baby and said: “What name will you give her?”

“We do not know yet; we haven’t consulted about it.”

Then some of the friends of the young people came up and put in their word.

“Why not call her ‘Olbia?’ It’s a pretty name; the name of this ship,” said someone.

The hint was immediately found satisfactory, and it was decided to name the little one as suggested. So as soon as the immigrants are allowed to land, there will be a procession of the newly-arrived Italians escorting to a church THE SEA-BORN BABE and she will be christened Maria Olbia, for with the Italians, fervent Roman Catholics, there must always be the name of a saint to accompany other names given to a child.

-The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, Louisiana) 09 July 1900

The Process

The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana) 09 July 1900 (Monday) described it as follows:

The first examination to which the immigrant is subjected is the rigid medical examination made by the Marine Hospital surgeons. The passengers having been sent to the rear of the ship, are called up one by one as their names are read from the manifest.

Under the escort of an inspector, they are ushered to the table where the physicians have their eye, ear and other testing instruments. The doctors begin the physical examination by testing the subject’s eyes, for infirmities of the eye cause more rejections than nearly all other physical ailments combined. After the surgeons have satisfied themselves that their subject’s vision is not impaired, they test the hearing, the heart, and look for malformation of the limbs, which is also the cause for sending a good many of them back as the government does not care to admit people of weak constitutions, who may become inmates of hospitals or other charitable institutions.

If the patient passes the critical inspection of the doctors, he is told to pass down the deck to that section of the ship allotted to those who are found to be up to the physical standard; if he is found to be infirm he is sent to another part of the vessel.

As each man, woman or child comes before the doctors they hand to the interpreter who checks their names a slip, known as the consular card. On this slip is the name, age, sex, and nationality of the immigrant. In addition to all this is the certificate of the ship’s surgeon as to the health of the immigrant during each day of the voyage. When the party named in the card is found to be in good health, the card is so indorsed by the physicians; if not, a slip giving the diagnosis of the case is attached and later turned over to the commissioners, who present it to the Board of Special Inquiry. This board makes a more exhaustive examination into the case, and upon its finding depends whether the immigrant be sent back to the port of embarkation or before the physicians a second time for examination.

After the physical examination comes the examination of the commissioners, and this is equally rigid, as it is practically the last, and definitely determines whether or not the applicant gains admittance.

The scheme of questioning one is practically as follows: “Have you relatives here? To what place are you going? Have you enough money to carry you there? Were you ever in this country before, and did your father, mother, or husband or any relative write to you to come, and did they agree to pay you so much per day to work for them or declare they could secure any specified amount of salary for you?”

Especial importance is attached to the inquire as to whether or not any relative had written the immigrant to come to American or not, and what price they were told they could get for their services. If any price be named as compensation for the would be American he is sure to get the letters “C. L.” marked after his name. The letters mean contract labor, and to come to this country expecting to get a certain price for any work is fatal to the chance of the immigrant for the immigration laws of the United States strictly prohibit any foreigner coming here to fill a contract made in any country.

{Note: Contract Labor did occur, and that’s how some immigrants were able to obtain tickets particularly since the prices were so high (around $1,000 in today’s money for steerage accommodation which was the least expensive option). That’s why the passenger records ask who paid for the ticket, and for all who were admitted it either says “by him” or “by her.” It does seem, however, that if it were family who were offering the immigrant the job, that should not have been the same category though it sometimes was interpreted that way.}

Summary from The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, Louisiana) 09 July 1900 (Monday):

After eight hours of steady examination, the day’s labors were brought to a close, and the government officers returned to the tug and were conveyed back to the starting place. They will return to-day to resume the task and will try to expedite the ordeal as rapidly as possible. Until every one has been thoroughly examined the Olbia will have to remain in midstream.

Locals Waiting for the Passengers

From The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, Louisiana) 09 July 1900:

The arrival of the immigrants is creating considerable excitement among the Italian population of this city, because there are many of their friends and relatives on board of the Olbia. All day yesterday large numbers of voluble, nervous sons and daughters of Italy crowded the Northwestern Railroad wharves and strained their eyes in their attempts to distinguish some familiar face or form on the decks of the Olbia standing far away near the “Point,” too far, in fact, to allow any one to make out anything but the hull and rigging and outlines of the vessel.

Many of the home Italians went out in skiffs and circled around the Olbia. Then the scene was well worth witnessing. As soon as one of the people in the skiffs caught sight of a friend on board the Olbia, whose decks were swarming with scores of wildly-gesticulating Italians, also peering into the flotilla of small boats with intent to discover a relative or a friend; as soon as recognition dawned then there was a whoop and a hurrah and loud and shrill appeals and calls, “Ah! Pedro; oh Jaquento; eh! Maria, Antonia,” etc. As the skiffs came nearer and the recognitions more frequent, it was comical to hear the confusion of tongues, the babel of voices, which made such a din that the captain had to enforce silence by ordering the immigrants to keep away from the rails.

During the hubbub a young woman espied her husband on one of the skiffs, and was so overjoyed and surprised that she sprang upon the rail and probably would have fallen overboard and been drowned, but for the quick action of a fellow-passenger, who seized her bodily and compelled her to regain the deck. United States Inspectors Harris and Huey will remain in charge of the Olbia until the examination is completed.

From The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana) 09 July 1900:

There were many scenes and incidents witnessed by those aboard the Olbia yesterday which created an indelible impression in the minds of those who witnessed them..

From early morning till late in the evening the river was alive with small boats of all descriptions. This mosquito fleet swarmed around the vessel, and it was with the greatest difficulty that the force of inspectors managed to keep the occupants of the skiffs, launches and every other imaginable kind of boat from attempting to scale the sides of the ship when they recognized some friend or relative they had not seen for years, and for whom they had long before come to this new country to make a home.

A young woman was standing near the bow of the ship, eagerly scanning the faces of those who paddled around the vessel and kept up an incessant jabbering with those whom she recognized. Suddenly she threw up her hands and with a scream attempted to throw herself over the side of the ship. She had seen her husband. They parted seven years ago in Italy, two weeks after they were married, and now the wife comes to join her husband and take up again the interrupted honeymoon. This was only one of the many instances of a similar character, and the inspectors had all they could do to repress the excitement of the relatives in their eagerness to meet their kin.

One woman told the interpreter that her husband had been in America twelve years, and that now she was coming over to spend the remainder of her life with him. The seventeen-year old daughter, who barely remembered her father when he was pointed out, dropped on her knees and with the tears streaming down her face, began to pray. The excited father waved his hands and several times tried to swing himself aboard the ship and could scarcely be detained in his boat.

A young married couple who came over together were among the most conspicuous passengers aboard the Olbia. The reason for their elation was the fact that the wife had given birth to a very robust girl babe. The proud mother, racing from one side of the ship to the other, exhibited the child to everyone and insisted that Commissioners Montgomery and Levy should be made to know the chubby little girl was named Olbia and that she would grow up in America, “our new home,” as they call it.

Landing

From The Times Picayune (New Orleans, Louisiana) 10 July 1900 (Tuesday):

The First of the Olbia’s List to Land To-Day.

Sunday they passed 120 immigrants through the formal interrogatories. Yesterday the task was easier and more rapidly prosecuted. Two hundered {sic} were examined, leaving about 200 yet to be inspected.

It is expected that the Olbia will be allowed to come to the Northeastern wharf this afternoon to allow such of the immigrants as have successfully passed to land.

From The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana) 10 July 1900 (Tuesday):

The preliminary inspection of the 600 and odd Italian immigrants who arrived Sunday from Palermo on the steamship Olbia was concluded yesterday by Commissioner Samuel Montgomery of this port, assisted by Commissioner W. T. Levy of Galveston and Drs. Schereschewshy and Scott of the Marine Hospital Service.

As a result of the inspection 150 of the new arrivals were provisionally detained and ordered to report for further investigation to the Board of Inquiry will meet at once.

This does not mean that the entire 150 will be barred out of the United States. A large proportion of those who failed at the first instance to pass were detained under the provision of the law which forbids the landing of immigrants who are “liable to become a public charge.” This included a number of married women whose husbands are here and will probably turn up inside the next twenty-four hours and satisfy the authorities of their ability to maintain their families. Others are men who depend on relatives to assist them in obtaining employment, and altogether it is likely that the actual number “turned down” will not exceed thirty or thirty-five.

From The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana) 11 July 1900 (Wednesday):

The Olbia landed fifty or sixty feet below the sheds of the Illinois Central Railroad, and the forces of Commissioners Montgomery and Levy, who were examining the immigrants to determine their eligibility to enter, and the customs officials who were searching and assessing the duty on imported goods, were forced to work in the broiling sun. Deputy Surveyor Nat Marks is authority for the statement that the total revenue derived from assessments made on dutiable goods will amount to over $200.

The Olbia’s passengers presented rather a woe-begone appearance as they stood grouped along the wharf watching the customs officers going through their effects. To enumerate the stuff they brought would require several columns, for there was everything in their luggage from Angora goat hair to new maccaroni {sic} machines. One family, composed of father, mother and three children, had enough stuff to stock a small general merchandise establishment. Among their effects were bird seed, shoes, a number of pairs of socks, silk and cashmere shawls, a maccaroni {sic} machine and a various assortment of handkerchiefs and scarfs {sic}.

Notwithstanding the fact that there was no protection for the women and children from the blistering sun rays, no one sustained a sun stroke, but it was a pitiful sight to see the poor little children and jaded looking women suffering from the heat. The government officials were as considerate of them as possible, but with the exception of the small awning stretched over the decks of the Olbia amidships there was no place they could send them where they would be protected from the heat.

Capt Mattel of the Olbia is much distressed over the long and expensive delay his ship has had here. The captain says that while he realizes the fact that the delay is unavoidable, it will prove expensive to this company, as he has a large cargo of fruit which, if not unloaded soon, will be greatly damaged.

From The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, Louisiana) 11 July 1900 (Wednesday)”

The Olbia was released from her anchorage off the point near the lower anchorage off the point near the lower limits of the city at an early hour yesterday forenoon and steamed up to the Thalia street wharf.

As the vessel was taking her berth, an immense crowd assembled, filling every inch of space on the landing, and providing a most inconvenient obstacle to the preparations of the United States customs inspectors and the police, who were engaged in parking off a generous space between the stoutly-stretched ropes, so as to exclude the general public from the wharf at which the Olbia was being moored. After much shouting and bustling, and the distribution of a few taps with clubs on the heads of the more obstinate in the mob, the policemen succeeded in clearing the space between the ropes—a space comprising the whole length of the wharf, from bow to stern of the Olbia, and the whole width of the landing, from apron to bulkhead.

(Wait a minute. Did they say “a few taps with clubs on the heads of the more obstinate in the mob?” Yes they did. Apparently those overly eager to see their newly arriving relatives who were still being held on the ship days after arrival were “tapped” on the head with clubs.)

Soon the outer edges of the hollow square began to fill with sons and daughters of Italy, resident of this city, aligning themselves, with supreme indifference to the heat and dust, and looking with eager eyes towards the vessel, which contained either a relative or a friend. Cries and frantic gestures announced and emphasized the recognition from those on land to those on board the ship, and frequent were the vociferous calls, “Al tanto! al tanto” (after a while), meaning that ere long there would be a meeting and an effusive embrace between the impatient, waiting friends on shore and the expectant immigrants on the Olbia.

As the noon hour arrived, there was a perceptible increase in the crowd on shore; a sensible augmentation of caloric in the sun’s rays, and the atmosphere became heavy and oppressive. Big, white-capped, frowning thunder clouds began to raise their battlemented heads above the horizon on the left bank of the river, while similar vapory and ominous, gray clouds were slowly ascending from the direction of the city suburbs. Frequent rumblings of thunder from those two opposite fields in the sky presaged a storm. The sun was gradually obscured. A breath of warm, moist wind came coursing across the bosom of the river and added its uncomfortable dampness to the perspiration that was trickling in tepid drops adown the cheeks and necks of the people on the wharf and aboard the ship.

Lightning flashes began to rend the heavy curtains of clouds which were rapidly rising which now loomed directly over Algiers. On this side of the river the heralds of the storm were also zig-zagging their pathway among the rolling masses of vapor, and it looked as if an atmospheric disturbance of some violence was about to break over the city.

But beyond a few brilliant thunderbolts and some rather sharp peals of thunder and a sudden brisk wind that whirled and lifted up to a considerable height mountains of dust, no storm was experienced, and after a short and slight fall of rain the sky cleared again and the rays of the sun bore down with seemingly increased fervency. There were signs, however, of a copious rainfall two or three miles beyond the Algiers bank, and to one who was observing the heavens in the direction of the city suburbs it appeared as if rain and wind and lightning were playing sad havoc over there.

Apprehension of a downpour and of the expected thunderstorm had driven the crowd from the wharf to places of shelter under the sheds and the awnings. With the return of calmer weather the people came back to the wharf and again stationed themselves outside the roped space.

The Olbia presented a scene of constant bustle and activity all day. From 11 o’clock a. m. until 6 p. m. the officers of the government were in full possession of the vessel.

Mr. S. A. Montgomery, the commissioner of immigration, and his assistants, Messrs. Levy and Martocci, were completing the examination of the immigrants. While these gentlemen were thus busily engaged, calling names, interrogating the Italians, refusing or allowing admission, another set of government deputies was at work inspecting the baggage of the immigrants who had received permission to land. This part of the programme devolved upon Messrs. Harry W. Robinson, chief deputy surveyor of the port; Nat L. Marks, acting deputy collector; Eugene Perroncel, assistant appraiser; Chris Madden, chief inspector of customs.

It was one of the hardest and most inconvenient of tasks, this inspection of baggage. The heat aboard ship was intense; the noise and cries and protests of the immigrants as the inspectors opened and examined each piece of baggage were added items of discomfort, and at intervals the men engaged in that fatiguing process were compelled to stop from sheer exhaustion and take turns in rushing on deck for a breathing spell.

Several articles of jewelry and a number of odds and ends, ornaments, fancy boxes, were set aside as dutiable, much to the chagrin and astonishment of the owners. But the interpreter explained that by paying the duties the owners could secure the release of their property within twelve months.

The inspectors found that the immigrants were possessed of a fair quantity of wearing apparel and personal property. They seemed better off in those articles than any previous batch that has come to this port. The duties collected up to the time the inspection closed, at 6 p. m., were a little over $200. It should be stated that all articles under $2 duty value per individual were, under the law, admitted free.

Commissioner Montgomery and his assistants worked heroically and under great difficulties yesterday. There was absolutely no accommodation enabling them to conduct their examinations. It was not only a hardship to them, but positive cruelty to the immigrants. The government officers were cooped up under a canvas tent over the main hatch. They were exposed to the rays of the sun as they were reflected from the river and they suffered from the heat which pierced through the thin canvas of the shelter and created an atmosphere of unpleasant warmth, mingled with the damp and tepid exhalations creeping up from the fruit-laden hold of the ship.

And the immigrants—poor souls! It was pitiful to observe their plight. They were aligned on the deck of the vessel in a long, serried procession, on both sides, from amidships forward, awaiting with the anxiety and under a broiling sun with the call of the interpreter summoning each immigrant in turn to step forward and submit to the question mill.

Most of the Italians were dressed in clothing utterly unsuited for a warm climate; the men in corduroy suits, or in heavy velvet coats and trousers; and women in thick woolen dresses, and some even wearing shawls. Their distress was evident, but there was no help for such a pitiable state of affairs.

NEED OF AN IMMIGRANTS’ STATION

From The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, Louisiana) 11 July 1900 (Wednesday):

“Until the government shall build an immigration station at New Orleans,” remarked Commissioner Montgomery, “such scenes as you see here to-day are bound to occur. I wish some official from the central office were here to take notes of the actual misery entailed by the lack of proper accommodations. The difficulties are such that not only do they give the government officers double work, but they bring great discomfort and suffering to the immigrants, besides causing loss of time and money to the vessels bringing the immigrants.

“Yes, sir,” continued Mr. Montgomery, “a station should be built with ample storage-room for baggage and with plenty of rooms for the immigrants, so that as soon as the ship lands the immigrants can be taken ashore and transferred to the station, thus allowing the ship to discharge her freight, or to seek some other landing, or in fact, go wherever her captain desires. The commander of the Olbia and his officers have been exceedingly clever and courteous towards the officers of the government, although we feel that they have been delayed and vexed by the examination which we are bound to make, according to the provisions of the United States laws.”

From The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana) 11July 1900 (Tuesday):

A prominent government official who is well posted in all matters appertaining to the entry of immigrants into this country, in conversation with a reporter yesterday, said:

“It is an outrage that the government does not provide some sort of accommodations at this port for the receiving of immigrants. Under the present arrangements we have no place to receive them, no place to land them, except some of the steamship wharves; and, in short, no means of handling them properly. Now when one stops to consider the matter and realizes that the immigration fund is the result of charges made by this government on every man, woman and child who comes into an American port, it is obvious that it is nothing but justice that the immigrants be provided with proper accommodations. One dollar is collected from the steamship companies who transport the immigrants to this country for each passenger and out of this fund the expense of handling them is defrayed. I have talked with several customs officials about the matter, and they all agree with me in thinking that some steps should be taken to bring the matter before the proper authorities in Washington.”

The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana) 12 July 1900 (Thursday) discussed the conditions endured by passengers due to New Orleans having no immigration station.

The treatment of the steamer Olbia and her freight of between 600 and 700 Italian immigrants at this port, since the vessel arrived here last Saturday morning, is nothing less than disgrace to a civilized government.

It has been cruelty to the immigrants to begin with. These poor people, before they are allowed to land, have to take their places in long lines on the deck of the steamer, and stay there until their turn has come for them to be examined, no matter what the temperature or the state of the weather may be. Our readers know what the temperature has been during the past four or five days, and they must therefore have an idea of the amount of suffering which the newcomers have undergone, as they have stood there with a blazing midsummer sun beating pitilessly upon them, and not even a suspicion of the shade in which to avoid the torrid heat. The United States examiners, it is true, have been in pretty much the same uncomfortable plight; but the examiners are dressed for the weather—which the immigrants are not, and, besides, the examiners are exempt from the racking uncertainty about their immediate future which, in the case of the immigrants, must add greatly to their distress both mental and physical.

New Orleans is one of the recognized immigrants’ ports of the United States, and year after year shiploads of foreigners coming to settle in this country land in this city. Yet the government has apparently never thought of building or acquiring such a place as an immigrants’ station in the harbor, to which the immigrants might be transferred as soon as the steamer comes to the wharf, and in which they might have simple accommodations until such time as the examiners had passed on their claims to land, and had either accepted or rejected them. Other ports have their immigrants’ stations, and why should New Orleans not have hers? What have the unfortunate newcomers who land here done that they should not meet with the same decent treatment that newcomers landing at other ports meet with? American citizens who have valuable horses and dogs would not allow their animals to be detained on board the unsheltered deck of a steamer for a number of consecutive days under a blistering sun at the bidding of any government in the world; and yet the American government has no scruples in subjecting hundreds of poor men and women and children who have come for the first time to our so-called hospitable shores to treatment to which Americans would never subject their four-footed beasts.

Not only does the want of an immigrants’ station subject the newcomers, and in a minor degree the examiners, to much and unnecessary discomfort and distress, it is also the cause of injustice and loss to the steamers which carry the immigrants as part of their cargo. The steamer Olbia, which brought the immigrants under notice, brought also a half cargo of fruit; had there been an immigrants’ station here to which she could have at once transferred her human freight, she could have gone at once to her wharf and unloaded her more perishable freight. As it is, the vessel has been five days out in the middle of the river waiting for this government examination to be over; and it is perfectly certain that part, if not the whole, of her fruit cargo will have gone wrong owing to the delay. Fruit cargoes keep while a vessel creates a draft for herself in her hold while she steams through sea or river; but when she comes to a standstill in a temperature like ours, decay of the fruit soon sets-in, and proceeds with great rapidity.

And thus, the lack of an immigrants’ station, as it causes distress to the living freight, so also does it cause injustice to the owners of the vessel and loss to the owners of the cargo.

If New Orleans is to be continued as an immigrants’ landing-place, it must have an immigrants’ station provided by the government; for the scenes which have been enacted on the Olbia’s deck these last five days must not be repeated, or foreigners will cry “shame” on our humanity.

From The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, Louisiana) 14 July 1900:

Government officials, ship captains and all persons who had occasion to note the delay, the tediousness and discomfort of the crude methods employed in receiving and disposing of the Italian immigrants who arrived on board of the steamship Olbia, unite in the opinion that until New Orleans shall have an immigration station there will be a positive hardship on United States commissioners and inspectors; a reprehensible cruelty to immigrants, and a costly loss of time to ships in the receiving of immigrants at this port. Five days were consumed in the examination of the Italians on the Olbia under the most uncomfortable conditions, such as warm weather, crowded decks, and vexatious slowness of the investigation.

Captain Felix Mattel, commander of the Olbia, was outspoken in denouncing the lengthy ordeal, and frequently expressed his surprise that New Orleans was so far behind in “civilized usage.”

Mr. S. A. Montgomery, the United States commissioner on immigrations, said that he was utterly exhausted with the labors of the past week, and that his feelings were shared by his assistants, Messrs. Levy and Martocci.

“New Orleans should have an immigrants’ station,” earnestly remarked Mr. Montgomery. “The government could easily make some arrangement with a steamship company or with a railroad company to build a station and sheds for the special accommodation of the immigrants, and pay a yearly rental for the same. There are $20,000 to the credit of the immigration bureau in New Orleans, and out of that sum the expenses of maintaining the station could be easily met. Each immigrant pays $1 per captita tax which the government credits to the immigration fund. Why not apply some of that money for the building and maintenance of an immigration station?

“This is an important matter for port of New Orleans whose commerce is bound to suffer and whose good name will be deprecated should the sights and scenes and confusion and suffering that marked the arrival and landing of the immigrants on the Olbia be repeated.

From The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana) 19 July 1900:

The arrival of the Olbia with its great load of immigrants and subsequent formalties attending their landing has directed attention to the wretched facilities which exist at this port for such work. The vessel reached the Point at 4 p. m. Saturday, the 7th. In addition to nearly 600 passengers, she had on board a large cargo of perishable freight, mostly Italian table delicacies, and 3000 boxes of fruit. She was unable to proceed to the wharf and discharge this stuff until the immigrants were disposed of, and the consequence was that it suffered severely while the ship was lying motionless in the intense heat, with no possibility of ventilation between decks.

The regular inspection began Sunday at 11:30 a. m., and was not concluded until Tuesday noon, when over 500 were allowed to land, 65 being held for special examination. These poor people had been kept for three days in the blistering sun, spending most of the time on deck, as it was impossible to exist in the stifling heat below. Their sufferings were frightful, and many of the crowd were delicate women with small children. The dark space was entirely inadequate for their accommodation, and they stood huddled together like sheep, without shelter or facilities for ordinary cleanliness or decency.

The scenes enacted during that trying period were pathetic and shocking. Every day women fainted from heat and exhaustion, and some of the smaller children lay in a dead stupor. It is surprising that there were no deaths then and there, and what the consequences of such an ordeal will be nobody can say. While the examinations were in progress the odor arising from so many people packed in such a small compass was nauseating. Some of the officers, inured to similar experiences as they are, were obliged to leave frequently for fresh air.

The sixty-five who were held suffered a considerable prolongation of the torture. The special examination was not over until Thursday at 6 p. m., and the consequence was that they were detained for six whole days. Some of them were so exhausted when they were finally discharged that they had to be assisted in leaving the ship.

The real trouble is that New Orleans has not proper facilities for handling large bodies of immigrants. In New York such human cargoes are landed immediately at the Barge Office, where they are comfortably quartered while the inspection is in progress and the vessel is meanwhile enabled to discharge whatever freight it may have on board.

“What we ought to have,” said a steamship agent yesterday, “is a good sized wharf somewhere between Chalmette and the Slaughter House. It should be roofed over and be furnished with suitable offices for the inspection of immigrants. When a ship arrived it could draw up alongside at once, discharge its passengers and go about its business. Such a wharf would cost but very little, and would not only do away with an immense amount of acute human sufferings, but would be a great boon to the ship owners. It ought to be erected at once, in the interest of both commerce and humanity.

Summary, Stowaways, and Fines

From The Times-Democrat (New Orleans, Louisiana) 25 July 1900 (Wednesday)”

Originally there were twenty-five Italians to be sent back to their own country, but only nineteen were deported. Three were released by the local government officials and three escaped by jumping overboard and escaping in skiffs which were in waiting. The first foreigner to escape got away three or four days ago. Strict watch was kept on board the Olbia, but the sly Italian waited for an opportunity when nobody was looking, and he leaped into the Mississippi. Before the officers of the ship could realize what happened, the Italian, dripping wet to the skin, was being rapidly rowed away in a small skiff, which was kept at a safe distance from the Olbia. It was too late to pursue the escaping Italian, and in a short while he was soon out of sight.

There were two other Italians who came all the way from Palermo who were determined not to go back to the country from which they came. They, too, apparently had friends in the city, for on Monday afternoon when they jumped overboard they were picked up and rowed away by men who were waiting in skiffs.

The agent of the steamships who transport the foreigners to this port are responsible for the Italians, and are heavily fined for every one that escapes. The agent is fined $300 for every one that escapes, and as three escaped from the Olbia while lying at this port, the agents of the Olbia will be called upon to pay the sum of $900.

The Olbia had to pay an additional fine of $2000 for violation of the navigation laws of 1882 relative to transporting more immigrants than there were berths aboard the vessel. The Olbia could accommodate 527 passengers, but in two of the apartments there were forty persons, twenty in each apartment, making a total of 677 foreigners brought to this city. The immigration law provides that the master of a vessel coming to a port or place in the United States in violation of the provisions of the section shall be guilty of a misdemeanor. The fine in this instance is $50 for each person that the master does not provide a berth for, and there were forty more than could be accommodated, a fine of $2000 was imposed by Collector of the Port Capt. A. T. Wimberly.

From The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, Louisiana) 25 July 1900:

The visit of the immigrant ship Olbia to this port will be memorable to the officers and owners. She has had a vast amount of trouble, and now has large penalties to pay, besides keeping twenty-five immigrants for several weeks and taking nineteen back to Italy, because they were not eligible to residence in this republic. The inspectors rejected twenty-five at the onset. Some of these appealed their cases to the commissioner of immigration at Washington, and he allowed three to land and they were released on giving bond that they would not become public charges. That left twenty-two, but three escaped from the ship, one three days ago and two yesterday. Therefore, the captain had to pay the $300 each that the government requires of a ship which allows passengers of that sort to escape.

The ship also had too many passengers in a given space… and for each… was fined $50, and that makes $2000, and $2900 in all. The Olbia cleared yesterday and left about 2 o’clock for her home port.